The Brooklyn Museum is preparing to return about 4,500 pre-Columbian artifacts taken from Costa Rica roughly a century ago.

Costa Rica had made no claim to the objects, which were exported in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by Minor C. Keith, a railroad magnate and a founder of the United Fruit Company. And there were none of the conflicts, legal threats or philosophical debates that sometimes accompany arguments between museums and countries that claim ownership of antiquities in their collections.

Instead, the museum simply decided that its closets were too full, overstuffed with items acquired during an era when it aimed to become the biggest museum in the world. So it offered the pieces to the National Museum of Costa Rica, which accepted but has yet to raise the $59,000 needed to pack and ship the first batch.

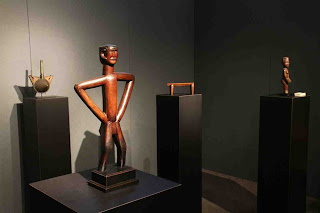

The objects that the Museum plans to let go are primarily made of ceramic and stone; they include bowls and other vessels, figurines, benches and ceremonial metates, or grinding stones. They are among 16,000 artifacts, some made of gold and jade, that Keith and his workers found on his Costa Rican banana plantations. About 5,000 of these pieces ended up in Brooklyn. The museum's plan to transfer some of the collection to Costa Rica was first reported in ARTnews.

The museum plans to keep some of the most valuable pieces, including gold and jade animals and anthropomorphic figurines and pendants. It is unlikely that many of the items being returned have ever been exhibited, although the museum’s records are not precise in that regard. Earlier efforts to give them to Costa Rican and American museums were unsuccessful.

“It’s exciting to find a home” for the objects, the museum’s curator of the arts of the Americas, Nancy Rosoff, said. “Hopefully they can come up with the money.”

The decision to part with most of the Keith objects is part of a culling of the Brooklyn Museum’s collection that has been under way for a decade. Museum officials once estimated the size of its collection as 1.5 million items, although they are revising that downward as records become computerized.

The goal of the culling is to remove works that are not being exhibited or do not fit the museum’s mission, and to reduce storage costs and to conserve staff members’ time. Kevin Stayton, the Brooklyn Museum’s chief curator, said it was an effort, at a time of strained budgets, to make sure that “we’re not overextending ourselves.”

The largest group of items to leave the Brooklyn Museum so far is its collection of costumes, 23,819 that were transferred to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2009. About another 4,400 objects have been deaccessioned already, including 983 Keith pieces. Ms. Rosoff said she expected ultimately to transfer 90 percent of the museum’s Keith objects to Costa Rica.

Like many American museums founded in the late 19th century, the Brooklyn Museum had an almost insatiable appetite for material. Known in its early years as the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, the museum was conceived as Brooklyn’s answer to the Metropolitan, and then some, with departments focused on natural history and the sciences as well as on art. It was designed to be the largest museum in the world, but after Brooklyn was consolidated into New York City in 1898, the effort lost momentum, and only a sixth of the planned structure was finally built.

The museum acquired the Keith collection in 1934, five years after Keith’s death. Keith, who was born in Brooklyn, had gone to Costa Rica in 1871, at 23, to join his brother in building a railroad from San José to the Caribbean Sea. During the project’s construction — which took two decades — Keith also established himself as one of the biggest growers and exporters of bananas in Central America. It was on one of his Costa Rican plantations, called Las Mercedes, that his workers first came across pre-Columbian gold ornaments, spurring the start of his collecting.

When the Brooklyn Museum first contacted the Costa Rican museum several years ago about the possibility of transferring most of its Keith objects, it received no response, so it reached out to American museums that had their own Keith collections: the American Museum of Natural History and the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History and National Museum of the American Indian. Perhaps unsurprisingly, since the Brooklyn Museum was planning to keep the cream of the collection, the other museums were not interested.

The Brooklyn Museum reached out to the Costa Rican museum again last year and that time got a positive response — though, in the absence of money to ship the objects, it leaves the timing of a transfer up in the air.

Since beginning a review of the Keith objects in Brooklyn several years ago, Ms. Rosoff has tackled only the ceramic materials and has not gotten through all of those. Among the objects she has chosen to keep are a vessel ornamented with the head, feet and tail of a tapir (a hoglike mammal with a long snout) and another piece, of unidentified function, embellished with a sculptured figure of an armadillo. The objects being sent back to Costa Rica are not of exhibition quality, at least not in an art museum, Ms. Rosoff said, but do have potential value to students and researchers.

To the Costa Rican museum, though, the transfer seems to be of primarily symbolic importance. Sandra Quirós, director of the National Museum of Costa Rica, said in a telephone interview that the museum did not have immediate plans to display the objects, even if it found the money to ship them. Instead the items would probably go into storage, where they would be available to researchers. She was enthusiastic, however, about regaining part of the country’s cultural patrimony.

“This wasn’t an initiative of ours — it came from outside — but once we were informed of it, of course it was of interest because this is part of Costa Rica’s history,” she said, speaking through an interpreter.

In some ways the transfer is not unlike the Metropolitan Museum’s recent decision to return to Egypt 19 artifacts from Tutankhamen's tomb. In that case the Met concluded that the objects had come to the museum in violation of an agreement intended to keep the contents of the tomb in Egypt. However, the objects’ minor significance — some were little more than bits of wood — made the return seem to be partly an easy way to garner some goodwill with Zahi Hawas, the forceful secretary general of the Supreme Council of Antiquities in Egypt.

Ms. Quirós said there were no legal issues surrounding the Brooklyn Museum’s ownership of the objects, since they left the country before a 1938 Costa Rican law restricting export of archaeological artifacts. Still, she said, she looked forward to repatriating the pieces whenever the museum could find the money.

Source: The New York Times